Operating Nextcloud Sovereignly: Why the "How" is Decisive

Nextcloud stands for digital independence, European data protection standards, and an open, …

Many confuse Open Source with sovereignty. Both are interconnected – but one does not automatically guarantee the other.

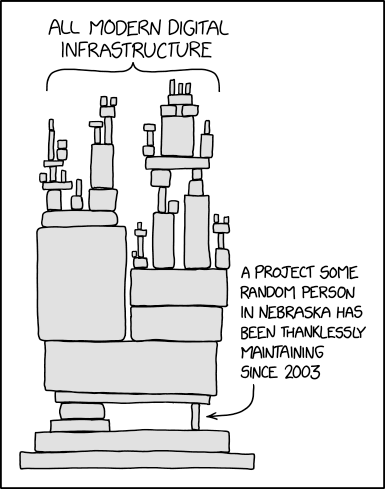

The well-known XKCD meme, depicting a vast, shaky digital infrastructure resting on a tiny software component “quietly maintained by some person in Nebraska since 2003,” is more than a humorous caricature. It is an accurate depiction of our digital present – and a warning to all who believe that Open Source automatically means security, control, or even independence.

Because the reality is: The code is free, the dependency remains.

Open Source is considered the epitome of technological freedom. Everyone can see, change, and further develop the code. The idea behind it: Transparency creates trust, trust creates stability, stability creates sovereignty.

In practice, however, a different picture emerges. Most Open Source components on which critical systems run – from Kubernetes to OpenSSL to log4j – are maintained by small, often overworked teams. Many of these projects rely on unpaid volunteer work or minimally funded maintainers who keep an infrastructure running on which billions of dollars depend.

This is not a technological problem but a structural one. Because sovereignty – whether individual, corporate, or state – does not arise from access but from responsibility. And responsibility only arises when resources, priorities, and ownership are clearly distributed.

Europe likes to talk about “digital sovereignty.” In strategy papers, at summits, and in funding programs, the buzzword is used inflationarily – mostly without a clear definition.

Often it means: “We don’t want to be dependent on US hyperscalers or Chinese platforms.”

This is understandable but short-sighted. Because sovereignty cannot be decreed. It is not a political state but a technological-organizational process.

The crucial question is not: “Who owns the software?” but: “Who understands, operates, and develops it?”

Europe has long relied on proprietary systems, then discovered Open Source – but often ignored the crucial layer in between, namely sustainable maintenance and operational competence.

The result: Many European organizations today host Open Source software in American clouds, without their own build chains, without reproducible deployments, without understanding the dependencies in their software supply chain.

The codebase is open – but the sovereignty lies elsewhere.

The term “software supply chain” has gained importance in recent years, especially since the attacks on SolarWinds and log4j. What was once considered a nerdy niche topic – dependency management – is now a central governance issue.

The reality: No modern company, no authority, no startup develops software entirely on its own. Every application consists of hundreds, often thousands of dependencies – libraries, frameworks, tools, Container images.

Each of these is potentially an attack vector or a source of operational risk.

And here lies the real contradiction: Open Source is supposed to create freedom, but often leads to uncontrolled dependency. Not because Open Source is insecure – but because organizations shirk the responsibility to understand, maintain, and actively shape these dependencies.

Only those who know what they stand on are sovereign.

Europe is an excellent user but a weak maintainer of Open Source.

Numerous authorities, research institutions, and companies massively rely on Open Source software, from Linux to PostgreSQL to Kubernetes. But only a fraction systematically contributes to further development.

This is not due to a lack of goodwill but to structural disincentives.

Research is rewarded for new insights, not for maintenance.

Companies finance features, not stability.

States promote “lighthouse projects,” not sustainable maintenance.

The result: The supporting components of the European IT landscape are often precisely those “projects from Nebraska” – metaphorically speaking – that are simply taken for granted here.

This not only endangers security and resilience but also the ability to innovate. Because those who do not understand systems cannot develop them sovereignly.

A widespread misunderstanding is: Digital sovereignty means that software “must originate from Europe.”

This is politically popular but technically irrelevant.

What matters is not the geographical origin but the operational access. A company or state is digitally sovereign if it:

A Kubernetes cluster on AWS is not automatically non-sovereign – but it becomes so if no one in the company knows how to build the same stack independently.

Similarly, software from the USA can be part of a sovereign infrastructure if it is transparent, reproducible, and verifiable.

Sovereignty is therefore not a matter of origin but of competence.

Open Source is often romanticized – as a community project, as an expression of digital solidarity. But in reality, it is primarily a governance model.

It regulates how power, responsibility, and control are distributed in software projects.

And that is what makes it economically interesting – but also complex.

Companies and states that use Open Source without understanding these governance structures are flying blind. They rely on “the community” without knowing who this community is, what interests it has, how decisions are made, who replaces maintainers if someone drops out, and who closes security gaps.

A sovereign approach to Open Source therefore means:

This costs money, but it is incomparable to the costs of outages, security incidents, or vendor lock-ins.

In Europe, the realization has slowly emerged that the state is not only a regulator but also an actor. Projects like Gaia-X, the European Open Source Cloud Foundation, or the Sovereign Tech Fund show that there is a growing awareness of the structural importance of digital dependencies.

But many initiatives remain half-hearted.

They promote short-term, evaluate long-term, act bureaucratically, and think politically. This is the opposite of what sustainable digital ecosystems need.

Sovereignty does not arise from funding notices but from operational excellence.

The state must understand that Open Source is not a welfare program but critical infrastructure. And critical infrastructure needs maintenance, monitoring, redundancy – and above all reliable funding.

Europe needs a “Public Digital Maintenance Policy” – a structural, long-term funding of central Open Source components, similar to roads, energy, or water.

Because digital infrastructure is no less vital today.

The cloud has intensified the discourse on sovereignty – and simultaneously exposed it.

Those who speak of “cloud sovereignty” often mean “cloud independence.” But that is illusory. Even “sovereign clouds” are based on international software stacks – from Linux to OpenStack to Terraform – and use globally standardized technologies.

Sovereignty in the cloud therefore does not mean isolation but manageability.

It is about reversibility, interoperability, transparency, and control.

An organization is sovereign if it:

This is not a nationalist project but a question of governance and engineering culture.

Europe’s technological dependency is not primarily the result of external dominance but of internal convenience.

Complex systems are gladly “outsourced” to avoid risks – and thus achieve exactly the opposite.

Many companies confuse efficiency with sovereignty.

A Managed Kubernetes Service is efficient – but only sovereign if one could also operate the architecture oneself.

A global cloud provider is scalable – but only sovereign if the switch remains technically and organizationally possible.

Sovereignty is not a luxury but an insurance against loss of control.

And like any insurance, it costs, but it only works when it’s too late.

So what to do? The answer lies not in isolation but in structure. Europe does not need to invent its digital sovereignty but organize it – on three levels:

Technically:

Economically:

Culturally:

Open Source and sovereignty belong together – but only if actively connected.

Freedom without responsibility is naivety.

Sovereignty without openness is isolation.

The art lies in balance: open, collaborative, and at the same time controlled, traceable, resilient.

The XKCD meme is therefore not only funny but deeply true:

The modern world stands on the shoulders of a few, often invisible people.

If we are serious about digital sovereignty, we must ensure that these shoulders no longer bear the burden alone.

This is not a question of ideology but of the stability of our societies.

And stability arises where responsibility is shared, not delegated.

Nextcloud stands for digital independence, European data protection standards, and an open, …

Kubernetes SIG Network and the Security Response Committee have announced the official end for …

Why Managed Kubernetes with Hyperscalers Doesn’t Lead to Digital Sovereignty Kubernetes has …